Eadric Silvaticus: Legend of the Wildwood & Shropshire Folk Hero…

The Eleventh-Century Saxon Thegn Who Became A Nineteenth Century Folk Hero

Eadric the Wild was one of the richest thegns (high ranking Saxon noblemen) in pre-Conquest Shropshire. He held land throughout the Welsh Marches and had much to lose following the Norman conquest. We know little about Eadric. Today his deeds are largely forgotten but his name survives through legend and folklore.

In 1067 Eadric submitted to William swearing fealty to him along with other Saxon noblemen, including Harold Godwinson’s grandson. He clearly changed his mind because he led an important rebellion against the Normans in 1069. William retaliated, devastating Eadric’s lands and Eadric finally surrendered.

Eadric was clearly a man William wanted on his side: he is last recorded as part of the king’s invasion host of Scotland in 1072. He then disappears from the record. Some suggest he was killed in action, others that he died in prison. But, there is also a theory that he is the Eadric of Wenlock, son of Aelfric, named as a tenant of Much Wenlock priory in 1086.

Eadric was a common name and so he was identified by the addition of se wilde, silvaticus, salvage, words all suggesting a fierce, wild temperament and an association with woodland. According to a twelfth century chronicle, the Normans called him le Sauvage, the Forester.

During the rebellion many men, Saxons and Welsh found themselves living as outlaw in woodlands and forests, avoiding capture and launching attacks. The Normans referred to them as silvatici or ‘of the woods’. This is possibly how Eadric got his nickname.

It is the Welsh Marches where Eadric is best remembered, where memories of Eadric haunt the wild and lonely Shropshire Hills. His reputation and notoriety perhaps ensured the survival of his name as a folk hero and it is impossible to study the folklore of this place without encountering Eadric the Wild and his bold knights.

I became more closely acquainted with Eadric while researching my thesis, through my old friend Walter Map and his rendition of a fairy bride story concerning Eadric the Wild. This is the earliest written account of a the Otherworld Bride motif known in Britain.

1. Walter Map & Edricus Wilde

In the late twelfth century the Anglo-Norman cleric, Walter Map, wrote a short tale concerning Edricus Wilde, clearly a man with a reputation …

‘so named from his bodily activity, and his rollicking talk and deeds, a man of great prowess; lord of Lydbury North’

Walter was an Anglo-Norman secular cleric and a royal courtier of Henry II. He was also a talented storyteller using old tales to create clever prose and narratives. Significantly, some of these tales relate to the unpredictable Welsh border and the colonization of the Welsh Marches. Amongst Walter’s surviving works is an account of the earliest known fairy bride tale, probably derived from similar Welsh tales. Eadric plays the leading role, possibly due to his notoriety and reputation that lingered amongst the local populace. It is a brutal tale involving the abduction and violation of an Otherworld woman by Eadric, Lord of Lydbury North, and his groom on their late return from a hunting trip.

The story goes that the two men come across a group of tall and graceful women dancing and singing in the woods…

‘most comely to look upon, and finely clad in fair habits of linen only, and were greater and taller than our women.’

Eadric falls violently in love with one ‘excelling in form and face, desirable beyond any favorite of the king’. He decides he must have her and attempts to steal her away from the others. There is a fierce struggle as the women fight to save her but Eadric and his page prevail. After three days of ‘using her as he would’ she concedes to marry him on condition that he never mentions her kin. The woman (she is never given a name) is visited by many including the Conqueror himself due to her exceptional beauty, cited as evidence of her ‘fairy nature‘ and Eadric is happy. But, as is often the way with fairy brides, Eadric breaks his vow, she disappears and he dies an lonely death.

Trying to understand medieval prose is sometimes like looking through a grubby window: it can be difficult to see through the layers. There are often subtexts and metaphors not always apparent to us modern readers. These tales may be better understood, and are often more interesting, when read in a wider social and historical context. In this narrative, the wildness and unknown nature of the woods and Otherworld women may refer to the turbulent unpredictability of nearby Wales: the Anglo-Normans and the Welsh had a very uneasy and unpredictable relationship exacerbated by the heavy handed barons, the Marcher Lords. Walter was acutely aware of the politics of this area and the impact of the Anglo-Norman yoke upon the populace.

But the ending of the tale gives us another clue. Walter concludes the tale by telling us that Eadric left an heir, Alnoth. Alnoth, who remember was half fairy, became very ill developing an incurable palsy. In desperation he visited St Ethelberts tomb at Hereford Cathedral, one of the most important shrines in England where his health was duly restored. Despite his fairy nature Alnoth prospered and spent the rest of his life as a pilgrim in St Ethelberts service. It was with great thanks to God and St Ethelbert that Alnoth presented his manor at Lydbury to the Hereford bishopry,

‘with all its appurtenances, and it is to this day in the lordship of the bishops of Hereford, and it is said to yield its lords thirty pounds a year’.

Walter Map, De Nugis Curilaium, Dist ii, c 12.

Now, Walter states that Lydbury North is in Wales but it is in fact in Shropshire, quite some way from Hereford. The original records for Lydbury had been lost in 1055 when the Welsh King Gruffydd ap Llywelyn sacked the city and it was forgotten how it came to belong to Hereford. Walter, a cleric of Hereford, likely wrote this piece to justify and explain how a Shropshire manor found itself in the possession of the Hereford Bishopry. Proof of land ownership could be a hot potato during these times, thus does Walter give credibility to Hereford’s claim!

It was not unusual for land ownership (or grabs) to be justified in this manner but by using the Otherworld/ fairy bride motif as a metaphor for the wild and unruly nature of Wales, the thorn in the side of the Anglo-Normans, the story also becomes a cautionary tale concerning the consequences of interference with resistant powers.

It is notable that Eadric was already attaining legendary status shortly after his own lifetime perhaps reflecting the reputation of the real man..

Orderic Vitalis & Edric Guilda ‘The Wild’

It was the twelfth century chronicler Orderic Vitalis that recorded that Edric Guida (Wild) had been received by King William at Barking (actually it was Berkhamsted) in 1067 with the other Saxon nobles. Eadric lost much of his land to the invading Normans, particularly Ralph de Mortimer, a huge humiliation for one of the most important and richest thegns in the Marches. And it seems that Eadric did not take this at all well.

Orderic wrote that ‘Eadric the Wild, a powerful and warlike man’, took up arms with the Welsh against the Normans causing many problems for the Normans. He joined the revolt of 1069 -70 leading a fierce resistance and laying siege to Shrewsbury, burning it to the ground.

Orderic was born and raised in Shropshire, his mother was English. Although he was using earlier records when writing up his chronicles he may also have been aware of oral accounts and anecdotes concerning Eadric. It is possible that Eadric was already a figure of legendary status.

Eadric seems to disappear for a few centuries until he emerges as a folk hero amongst the tales of the Shropshire Marches several hundred years later in the nineteenth century.

Charlotte Burne & Wild Edric

The folklorist Hilda Ellis Davidson wrote how folklore heroes are often those whose actions had a significant impact upon places and people. As a result they become linked with certain places and within accepted patterns of folk traditions. This seems to be the case of Eadric Wilde. It is significant that folktales concerning Eadric are primarily found in locations where he lived such as the area around the Stiperstones in the west of Shropshire. Here are preserved a number of traditions and we are indebted to Miss Charlotte Burne for collecting and writing down local remembrances of his stories.

In 1883 the Shropshire folklorist, Charlotte Burne published her book ‘Shropshire Folk-Tales’, a collection of folklore and tales gleaned from friends and the ‘Shropshire peasantry’. This comprehensive collection of stories and traditions includes tales of ‘Wild Edric’ recorded from those who, she wrote, believed Eadric was still alive, imprisoned in the mines beneath the wild hills in the west of the county, the Stiperstones.

Miss Burne wrote:

‘He cannot die, they say, till all the wrong has been made right, and England has returned to the same state as it was in before the troubles of his days. Meantime he is condemned to inhabit the lead-mines as a punishment for having allowed himself to be deceived by the Conquerors fair words and submitting to him. So there he dwells with his wife and his whole train. The miners call them the ‘Old Men’, and sometimes hear them knocking, and wherever they knock, the best lodes are found. Whenever war is going to break out, they ride over the hills in the direction of the enemy’s country, and if they appear, it is a sign that the war will be serious.’

Charlotte Burne, Shropshire Folk-Lore.

She continues how a servant girl reported how she had encountered Wild Edric and his men just before the Crimean war broke out in 1853. She was walking with her father, who had seen them before, and who told her to cover her face (not her eyes, significantly) and not speak else she would ‘go mad’. She said,

Then they all came by; Wild Edric himself on a white horse at the head of the band, and the Lady Godda his wife, riding at full speed over the hills. Edric had short dark curly hair and very bright black eyes. he wore a green cap and white feather, a short green coat and cloak, a horn and a short sword hanging from his golden belt…the lady had wavy golden hair falling loosely to her waist, and round her forehead a band of white linen, with a golden ornament in it.’

There are no records of a Lady Godda, or of Eadric’s wife. Miss Burne mused that ‘Lady Godda’ may be descended from a German goddess ‘Gode’ but concedes there is no evidence for this. Nevertheless there are some who maintain an ancient, pre-Christian pedigree for ‘Wild Edric’ and Lady Godda .

The Stiperstones are a dark and rugged place, with sweeping views along the Welsh border. The area has been mined for its lead since ancient times. There are many folktales here such as Mitchell the witch who was turned to stone and of the Devil’s chair which still smells of brimstone…sometimes.

And there are folklore motifs aplenty in Eadric’s tales: sleeping knights, black dogs, a Wild Hunt…

My husband’s grandmother had family from these parts, the Hayworths, some had worked in the mines. He remembers her telling the children tales of Wild Eadric and the ‘knockers’. The knockers are spirits or Otherworld folk who live down mines, knocking or hammering where there are good lodes or even danger. It is a familiar motif elsewhere in Britain in mining areas, especially in Cornwall.

Shropshire has several Black Dog stories, often associated with the supernatural and ghosts. Eadric’s ghost is said to haunt the Stretton Hills in the form of a black dog with fiery eyes.

A curious story is one from over Bomere Pool near Condover. It concerns a ‘Monster Fish’. This fish has lived in the mere for centuries and curiously wears a great sword by his side. Attempts have been made to catch the fish but without success. Once a huge net with links of iron was cast in order to catch the fish. Although captured he was able to cut through the iron with the sword and escaped back into the water! It is said that Eadric gave the sword to the fish for safekeeping before he disappeared, to be given only his rightful heir.

Eadric remains virtually unknown outside Shropshire. His resistance to the Normans and leadership of the revolt against them in the Welsh Marches is certainly worthy of a good song and story but his exploits seem to have been lost somewhere down the ages. He remains less of a figure from history, more folk hero leading a Wild Hunt with his Otherworld bride and his sleeping knights.

Nevertheless, Eadric continues to inspire storytellers and artists so his memory lives on.

Next time you visit the Stiperstones listen out for a tapping beneath your feet or a horn blowing in the wind…it may just be Eadric Wilde…

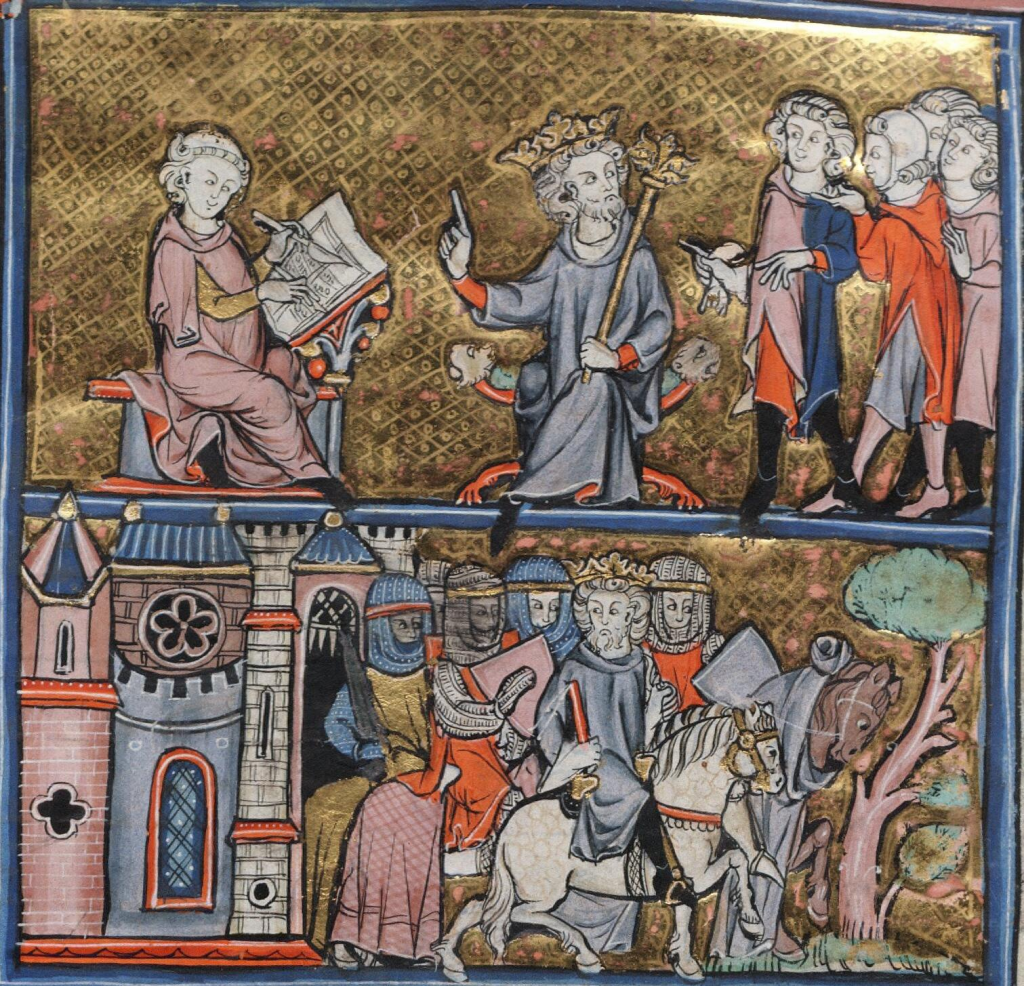

With special thanks to Tamsin Abbott for the use of her beautiful picture of Wild Edric…..

Further Reading:

Walter Map, De Nugis Curialium Courtiers’ Trifles (Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1983)

C. S. Burne. Shropshire Folk-Lore: A Sheaf Of Gleanings. Part 1

Amy Douglas, ‘Shropshire Folktales’