Tales from the Deep Earth: The Descent of Giants

Or, The Fall and Fading of Vadi…

With All Hallows behind us and the ever darkening nights of winter ahead, this is the time of year to dig in and burrow down into the warmth of home and hearth and listen to, or read, stories. Our folklore and legends are full of tales of giants but what happened to them between their appearance as fearsome primeval entities and the much later blustering entities uttering fee fi fo fum?

I wrote this piece last midwinter while researching tales and legends connected to the landscape. Many tales seemed to spring from the deep bones of the earth and often they concerned giants. Despite mythic and terrible beginnings nearly all seemed to devolve into the rather foolish giants of later folklore (see my blog https://myblog.moonbrookcottagehandspun.co.uk/2021/03/03/there-be-giants-in-them-blue-remembered-hills/ ).

The following is a story imagined from the remnants of those myths, legends and folktales. It explores how mythic characters continue to live on in our stories and how, perhaps, certain clues may be found hidden in ancient texts and later folktales. I will leave it to your good selves to join the dots and decide whether you can see any of the threads that run back through tale and time.

When I was Vadi….

On a high lonely moor in the north of Yorkshire there once lived a giant called Wade. Few remember him now but folklore tells how he left his mark, shaping and rolling the rocks and stones and bones of this high land.1

Wade had a wife, Bel. Together they would potter about the moors, building roads, throwing rocks. They also built castles. While Wade was building Mulgrave Castle Bel was busy building Pickering Castle and only having one hammer they threw it to each other across the moor as needed. It is said they had a child who threw rocks to get Bel’s attention when he wanted feeding.

Bel had a huge cow she kept on the far side of the moor. She had to traipse through the mud each day to milk her so to save her boots Wade built her a footpath. The path can still be seen today and is known as Wade’s Causey or Causeway. He worked hard building this road but Bel helped bringing him rocks in her apron. Sometimes the weight of the rocks was so great the strings would break, spilling the rocks into piles accounting for the many cairns up there. The cow’s jawbone, some say its rib, was once kept up at Mulgrave Castle in the old days.

There is a stone at Barnby called Wade’s Stone and said to mark Wade’s grave. The sixteenth century antiquary, John Leyland, noted other stones near Mulgrave castle known locally as Waddes Grave.2

These snips and snaps are all that are left of the folktales told around the hearths of homes and inns, at the fires of drovers and during Sunday picnics on the moors. As the machines spat and polluted the earth the descendants of those who bought him to these islands were too tired to remember him in their stories. Wade began to fade. until he finally lost heart.

But, if we look and listen very, very hard we can hear snatches and catches of older stories, stories that travelled across wide seas in the ships with tribes and traders from northern lands. These ancient tales, battered and fragile were carried on the mists of sea and snow, from lands where the Frost Giants once roared and raged and the old gods were held in awe and feared and pacified.

It was in these cold lands there had lived a sea-giant called Vadi. Vadi adapted and shifted so that he survived in mind and memories of ordinary folk and his tale twisted and changed until he was almost unrecognisable. Vadi survived longer than the rest of his kin but paid a lonely price.

Beginning…

There are many beginnings but the oldest was before the gods, before time began. Then there was nothing but a world of mist and a world of fire and between them a void where poisoned rivers flowed. These rivers froze between the mists and flames and here the ancestor of all giants was created in the ice that melted in the heat of the fires. This ancestor was called Ymir.3 Ymir was succoured by the milk of a giant cow also formed in the ice.

Ymir gave birth and all were giants.

Then Odin and his brothers murdered Ymir. Their actions created a huge flood and from Ymir’s remains a new world was created: teeth became rocks and boulders, seas his blood and clouds his thoughts. It is said every giant is descended from Ymir’s children.

And the remaining giants lived at the edge of this world.

It was thought that the giants all died at Ragnarök with the gods. But many survived in myths, shaped and moulded by the mouths of men and women who travelled down from the North. They crossed land and sea in great ships with great prows shaped like horses, riding the waves until they came to new lands where they told the stories from the lands of ice and fire.

With these stories came the great sea-giant Vadi.

Survival…

Vadi was happy that the people had remembered him. They had paid him homage asking for protection and safe passage as they crossed the seas in their bright boats, .

But the people began to forget their ancient stories as new ones were created by the mouths of men and women who chanted a new faith from the east. The frost giants and mountain giants started to fade becoming old memories in tales, remembered only as supernatural freaks lurking in shadows and mountains tops.

Men began to write down some of the stories, scratching them into skins of animals and hard stones. They told how Vadi’s father had been a king of Zealand, a land of islands and water. This king had met a ‘sea-woman’ (we would call her a mermaid) who became Vadi’s mother. 4

But there were older tales of how Vadi came from a line of ancient giants from the northlands, the lands of ice and fire. They told of his love of the salt waters and how he loved to stride across the straits and sounds of the Baltic Sea, sometimes with his young son, Velent, upon his shoulders like an ancient St Christopher.5

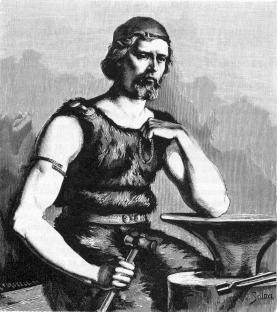

Vadi sent Velent, many know him today as Wayland, to the dwarves and he became a great smith. Velent also travelled with the tale tellers and eventually arrived upon the shores of Britain to make a name for himself here. For a while these and other giants were remembered. They were powerful, sometimes feared, walking and fighting their way through crackling fires and feasts of the great halls. Eventually many simply walked and fought their way into oblivion.

Legend…

So Vadi walked over the hills and through the mead halls of Britain and after hundreds of years of his telling through voice and song the tales began to be written down in cold ink . They became twisted, changed over the passage of years as each pen scraped away at the shadows of his being until Vadi became a shade of his former self. In time the mead halls were swept away by a new and harrowing force that came from across the sea. It bought with it scribes who used the fading stories to create new tales that sometimes held a glimpse or echo of a past being rapidly forgotten.

But Vadi held on, walking in the hills and the memory of these old tales. But as the stories were fixed upon the skins of beasts they became weaker, losing their potency and vibrancy. Vadi felt it too.

The stories changed.

Vadi became Gado, Wadi, Wade: sometimes a wild romantic figure, sometimes a hero embracing those qualities popular in times of reinvention and acquisition. His lost tale was captured in part by the pens and imaginations of new tale tellers such as Walter Map,6 Malory7 and Chaucer.8 Vadi is barely recognisable but if we look hard we can find him swimming between the words in his great boat with his love of the sea and his great deeds.9

And although Vadi tried to keep his head up after the Great Conquest the very men who should have recognised him, if they had paid heed to their ancestry, paid him too little attention. Vadi, now Wade, was now a shadow and tired. His ancient bones creaked and ached. He held on.

Yet these ‘middle ages’ still managed to keep his memory alive: the stories adapted and changed. The giants became figures of fun as great models were made to parade ecstatically through the streets during pageants and parades on feast and holy days.

Wade particularity like the feast of St John on Midsummers Eve when the citizens of Salisbury proudly paraded their giant they called Saint Christopher. The people vaguely remembered a story of a giant who carried his son on his shoulder across a northern sea. They could not remember his name and anyway, it was not seemly, they said, to celebrate this ‘heathen St Christopher’.10 Wade would smile at this. It reminded him of better times when he would stride out across the icy straits, to meet with others of his kin.

Finally, with the arrival of dirt and noise and smoke and machines, he gave up. The people had finally turned away. They no longer lived in sympathy with the natural world and with the primal and supernatural forces found between the folds of thought and time. Vadi felt stretched and tired. With his beloved wife Bel, he turned and walked away towards the Northlands to find a cave in which to sleep and dream and wait for all to pass. Then they will awake and return to the deep sea, to the lands of sea-giants.

So there they still lie, Wade and Bel, kept warm by their cow, and dreaming the dreams of giants.

And when the time is right, the cow will wake them, licking them into existence again as her ancestor woke Ymir did before the world began.

But only when the time is right,

Below are some of the references I used to follow Vadi’s journey through our imagination:

1 J. Westwood & J Simpson The Lore of the Land (Penguin: London, 2005) pp. 841-845. Also see entry in J Westwood Albion

2 ibid

3 See Norse sagas esp Snorri Sturluson 13c Poetic Edda. Handbook for poets about the Germanic gods. Many tales are based on old myths from the Viking era. (750-1050)

4 See Widsith OE poem ? 7th century. Also Thidreks Saga

5 ibid. Vadi is said to strides across the Groenasund, the strait between two islands. He sends his son, Velents, to learn how to be a smith from the dwarves

6 Gado. Walter Map. Earliest account written in England. Map may have adapted an existing tale. Offa is also mentions in Widsith

7 Morte Arthure. Also a dragon killer in Bevis of Hampton

8 Troilus & Cressida. Panarus’s tale refers to the Tale of Wade. Merchants Tale. Refers to wades boat implying it may be a magical one. See K. P. Wentersdorf ‘Chaucer & the Lost Tale of Wade (jstor)

9 Poem Of Kudrun. In Kudrun Wade is the ‘faithful retainer’ who gets the fleet to safety. The memory of this tale may have survived until the Middle Ages where it was still known in the oral tradition and referred to by Chaucer implying it was theb commonly known.

10 See http://www.salisburymuseum.org.uk/collections/medieval-salisbury/giant-and-hob-nob

2 thoughts on “Tales from the Deep Earth: The Descent of Giants”

I see the giant in the living earth bigger than humankind; and it is the gentle giant that speaks to me in your prose, the gentle giant that can roar and shout in anger of the cruel earth! But is the gentle giant that I look up to, as I have not been graced with hight, there are many giants who walk around me!

Yes – we need more ents I think!