‘Tis merry in hall, where beards wag all’…Traditions of Harvest

Come home, lord, singing come home, corn bringing. 'tis merry in the hall, where beard wag all.

The farmer and writer Thomas Tusser wrote these lines in 1557 referring to the great harvest feast held after all the crops were gathered in and safely stored away. An important culmination of the farming year right up until the last century, the annual harvest featured many rituals and traditions but, with the arrival of machines and other labour saving devices, many were obsolete by the end of last century. Today only the ‘harvest festival’ remains as a sober reminder of times when whole communities came together to celebrate and play.

By the 20th century machines were increasingly replacing the workers and many customs were lost and many songs forgotten. Those that survived were often obscure and shrouded in mystery, practiced by people who often had no idea of their meaning. There are examples of collectors helpfully putting their own ‘spin’ on a custom so care is needed interpreting some accounts. (It was not unknown for a person to make up a story for their own amusement !)

Few records of harvest traditions are known before the sixteenth-century and later examples tell us little about them. Oral traditions were disappearing quickly when antiquarians and early folklorists started recording, fixing them in print before they were gone forever. Many have strange names, ‘crying the mare’, ‘cutting the neck’, ‘kern babies‘, ‘crying largesse‘, their purpose or reasoning lost, forgotten or altered.

Cutting the Neck & Crying the Mare

‘Cutting the neck‘ signalled the end of the reaping when the last sheaf fell. ‘Crying the mare’ signalled the end of the harvest. ‘Crying’, ‘calling‘ or ‘shouting the mare’, wrote Charlotte Burne in the 19th century, was a ceremony performed by workers to let other farms know they had completed their harvest. The men taunted farms lagging behind and would send their ‘mare’, the last sheaf, to any farm not finished and they to the next and so on. The last to finish would keep the ‘mare’ the whole winter. These now rare traditions may still be found in tucked away places such as Padstow, Cornwall, where each summer a hymn is sung and a prayer of thanksgiving is said in Cornish before the ‘cutting of the neck’.

Some antiquarians figured that these traditions were derived from an ancient belief that the spirit of the corn field was contained within the last sheaf. It was driven from the field as the crop was harvested.

The name of the last sheaf varies: mare in Herefordshire, Shropshire, Wales, Hertfordshire; hare in Galloway; frog in Worcestershire.

In parts of Shropshire it was called ‘cutting the gander’s neck off’, the neck usually being twenty ears of corn. (Thomas Wilkinson of Much Wenlock (b. 1796) wrote of one ear of corn in a neck). The ears would be knotted together in the middle of the field when the rest had been cut and the men stood ten to twenty paces distant. They threw their sickles until one severed the last sheaf and so the ‘best mon’ won! A great shout would go up and it was time for the harvest feast!

On the Isle of Man the last sheaf was bound with ribbons and taken to the nearest hill where the Queen of the Mheilla, the Harvest Home, held it over her head to loud cheering.

These corn dollies were made by my grandfather over fifty years ago. They are tiny, about the size of your little finger. Corn dollies became a rather refined tradition with many different styles and regional variations. Their names vary also: kern-babies, ivy girls or mell dolls. Their origins are rather vague but they are likely derived from the last sheaf tradition, a trophy or token of the harvest. Many areas would decorated a large corn dolly in a child’s frock and ribbons. Sometimes it was carried by the ‘harvest queen’ to signal the end of harvest. The ‘craft’ of making corn dollies is on the ‘heritage crafts’ red list, a skill in real danger of dying out.

Fortunately there are some innovative and exciting new artisans breathing new life into the tradition such as Victoria Musson. Below is a ‘dolly’ I made on one of Victoria’s workshops at Blue Ginger Gallery, near Malvern last year.

See her website below for stunning examples of her work.

Not all places have records of last sheaf customs but instead have a tradition of Harvest home. Harvest home describes the last cart carrying the last load home decorated with ribbons and flowers, corn and, in East Anglia, the ‘harvest Lord’ on top. The horses were dressed as finely as the cart and sometimes accompanied with singing and music.

George Ewart Evans wrote that in East Anglia, the harvest lord was usually the foreman, elected by the men for the term of the harvest. His role was to negotiate with the farmer, terms and conditions for the workers. He also was responsible for collecting ‘largesse’. This was basically a means of extorting money from people to put towards the harvest supper! In East Anglia, it was called ‘hollaring largese’ and in Suffolk they shouted ‘largesse or revolution!’ at folk passing by the harvest fields.

Sometimes there was a ‘lady’ of the harvest. ‘She’ was actually a man and second in command; if the ‘lord’ of the harvest was absent ‘she’ would take his place at the head of the line of reapers. The origins for both the lord and lady of the harvest are unknown.

When the work was done there was feasting, drinking, Lammas fairs, games, wakes and midsummer fires. Historian Ronald Hutton writes these fires were derived from an important pre-Christian ritual, perhaps related to purification and protection plus older traditions of sun worship. This is exemplified by accounts (one going back to 4th century Aquitaine) of rolling fire wheels down hills during midsummer. The wheel is the most widespread symbol of the sun in prehistoric Europe.

By the nineteenth-century many traditions were left behind or ‘refined’ by the gentry and especially the church. The church adopted Reverent Hawker’s idea of a harvest ‘festival’ replacing the more riotous harvest feast. The new ‘festivals’ were more sedate than the ‘feasts’. Some of the songs survived, rescued in antiquity by song collectors and folklorists albeit often altered due to bawdy lyrics !

One of the best known songs is John Barleycorn, the personification of the barley crop and its journey from seed to death and conversion to ale and bread. The earliest written version is from the sixteenth-century.

Now, there came three men out of Kent, my boys, For to plough for wheat and rye, And they made a vow and a solemn vow John Barleycorn must die. ~ Trad.

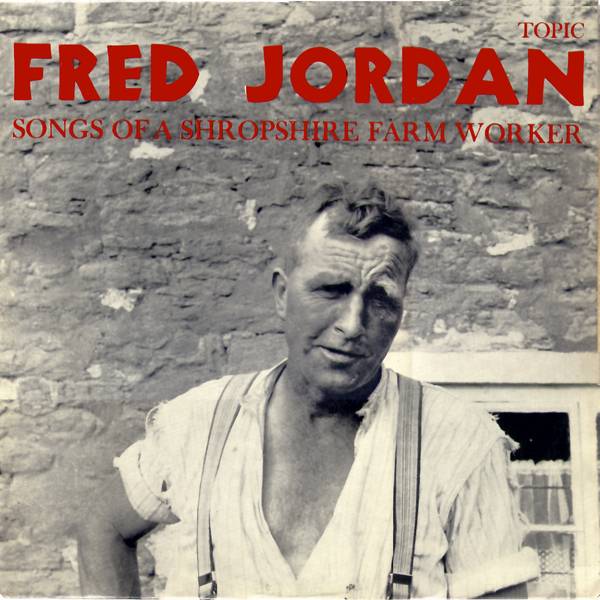

The Shropshire farm worker and singer, Fred Jordan, is known for his version of John Barleycorn. Forty odd years ago he use to sing in the pubs round here. Fred became well known amongst the British folk revival crowd, recorded by Alan Lomax and later, record companies, singing the old songs he learnt from the elders and local gypsies. Fred remained unchanged by his fame, growing veg and singing locally until bad health forced into a nursing home on the east side of the Hill where he died in 2002.

Fred wouldn’t recognise the area now. Machines do almost all of the farm work round here; gone are the singing sessions in the pubs and the lean, skilled farm workers have been replaced by giant tractors that tear up lanes and hedges. I never meet a farm worker when out walking like I did when a child: the old pub pipes music and serves mainly food rather than ale. But there are still a few that sing and celebrate the old ways.

Sometimes we find reminders. Once, Chris my husband found an old scythe hanging in a sycamore tree, rotten and full of woodworm. I sometimes wonder about that moment it was hung in the tree for the last time.

There are many dusty photographs of harvest working parties, taken in the nineteenth and twentieth-centuries. Grey faced men and women stare directly at the camera, clutching sheaves and scythes. Many of us will have ancestors amongst them: farm workers, helpful neighbours, farmers or land owners.

My mother’s family were farm workers moving up and down the Marches. They followed hop and cereal harvests, chasing the work up and down old roads connecting farm with village, part of a network of an itinerant work force: gypsies, travellers, farm workers and local people all sharing (or competing ) for work, all coming together to bring the harvest home.

What a time it must have been! The sense of urgency to get the oats, wheat, barley and rye in before the weather changed. The singing, the celebrations, the chance to mix with different people, people you knew but didn’t often get chance to chat with, parents and neighbours keeping an eye on the younger ones. A brief respite, perhaps, from hard labour and worry.

The grace and skill of the workers is captured on this rare 1915 film:

Although harvest customs are not known to have an ancient pedigree they were confidently described as having such by nineteenth-century folklorists who also connected them with the cycle of life, death and rebirth. This kind of interpretation remains popular today and it makes some sense but modern theorists conclude that harvest traditions are likely to be a celebration of hard work. It doesn’t matter. Folklore by definition is a shifting medium, shaped by the people and answering a need of the people. There is no time here to debate the complexities of the evolution of harvest traditions but there is a lot to be said for people coming together, now more than ever.

Edited.